Stages & Statuses of Transactions

Every payment follows a journey. What looks instant to a consumer (that quick "approved" message on a screen) is actually a chain of tightly orchestrated steps happening between several systems in just a few seconds. Let's walk through the typical happy flow first, the one where everything goes right.

The Happy Flow

It all begins when a consumer initiates a payment: either online or at a terminal. The merchant's system or payment gateway sends a secure authorization request through the acquirer and card network to the issuer, asking a simple but crucial question: Is this card valid, are there enough funds and can this card be authorized?

If the issuer approves, the transaction is authorized. At this stage, the funds are not yet transferred. They're simply reserved on the customer's account, waiting for the merchant to finalize them later. This reserved state prevents the same money from being spent twice.

Once the merchant confirms the order or ships the goods, they send a capture instruction. In some cases, this step happens automatically, without merchant approval. This tells the acquirer, "Yes, deliver the money now". The acquirer then groups multiple captures together and submits them to the card networks during clearing.

Finally, in the settlement phase, the actual transfer of funds occurs. The issuer sends the money (minus fees) to the acquirer, who then pays the merchant. This usually happens within one to three business days, depending on the merchant's settlement agreement.

In a perfect world, every payment would end right there: the customer is happy, the merchant is paid, and everyone moves on. But payments aren't always perfect — sometimes they're voided, refunded, or disputed.

When Things Don't Go as Planned

Not every payment has a happy ending. Sometimes customers cancel, transactions fail, or disputes arise weeks later. In payments, these "bad flows" are just as important to understand as the good ones. They reveal how risk, reversals, and customer protection work in practice. Let's look at the three most common exception flows: voids, refunds, and chargebacks.

Voids / Cancellations

A void happens when a transaction is cancelled before it's captured or settled. You can think of it as "undoing" an authorization that hasn't yet turned into a real transfer of money.

For example, a customer might cancel an order right after placing it, or a merchant might notice a duplicate transaction. In such cases, instead of processing a refund (which moves money back and takes a few days), the merchant can void the authorization.

Because the funds were only reserved and never actually moved, a void simply releases the hold on the customer's account. The cardholder's available balance returns to normal, usually within a day or two (or instantly, this depends on the consumer's bank!), and no fees are involved beyond the original authorization cost. In short, a void is a clean reversal: fast, efficient, and invisible to most customers.

Refunds

A refund comes after a transaction has been captured and settled. This means the merchant already received the funds, but now needs to return some or all of them. Refunds are common in everyday commerce: a returned product, a cancelled booking, or a billing error. They can be full (the entire amount) or partial (just part of the payment). Depending on the type of transaction only one or multiple refunds may be possible.

When a refund is triggered, the merchant's system sends a message through the acquirer and card network back to the issuer, instructing it to credit the customer's account. Depending on the network and banks involved, this process can take anywhere from one to five business days. And it may even take longer for the consumer to receive their funds (think of the issuing bank or merchant taking longer to process a request).

Depending on the gateway, a refund might be created as a separate transaction or as part of the parent organization within the merchant's management tool. In some cases, refunds may not be tied to a parent authorization. We can refer to those as unreferenced refunds.

While simple from the customer's perspective, refunds carry some operational cost for the merchant. Most acquirers charge small per-refund fees, and in many cases, the original transaction fees are not reimbursed. Frequent refunds can also impact a merchant's reputation with acquirers or payment providers.

Chargebacks

The chargeback is the worst-case scenario in the life of a transaction. It occurs when the issuer forcibly reverses a payment after a customer dispute. Here's how it typically unfolds: a cardholder notices an unfamiliar or problematic charge and contacts their bank to contest it. The issuer investigates and, if the claim seems valid, withdraws the funds from the merchant's acquirer: who in turn debits the merchant's account.

The reasons for chargebacks vary:

- Fraud or unauthorized use of a card

- Goods not received or services not delivered

- Items not as described

- Duplicate billing or technical errors

- Refunds promised but never received

For merchants, a chargeback is both a loss of funds and a potential signal of poor customer experience or fraud exposure. Each chargeback also comes with administrative fees. If the merchant believes the dispute is unfair, they can challenge it. This involves submitting evidence (such as delivery confirmations, receipts, or correspondence) to prove the transaction was legitimate. However, even when successful, representment takes time and effort. Repeated chargebacks can result in penalties or inclusion in card-scheme monitoring programs. Chargeback = no good. Best is to settle the dispute with the consumer first.

And Then There are Errors

Even the most carefully built payment systems stumble sometimes. Not every transaction reaches the finish line. Declines and errors are part of everyday payment life — the invisible friction behind "something went wrong". They can happen for hundreds of reasons, from something as harmless as a typo to something as serious as suspected fraud.

For merchants, these moments are frustrating; for customers, they're just confusing. The main culprits:

- Insufficient funds (≈ 30–40 % of declines) — the simplest and most human reason

- Issuer risk or fraud rules (≈ 25 %) — banks block what looks suspicious, especially cross-border or unusually large transactions

- Expired or inactive cards (≈ 10 %) — still surprisingly common

- Technical errors (≈ 10 %) — network outages, timeouts, or protocol mismatches

- Incorrect credentials (≈ 5–10 %) — wrong CVV, postal code, or 3-D Secure failure

Good providers mitigate this through smart retries, network tokenization, and intelligent routing. Even a two-point improvement in approval rate can mean millions in additional revenue for large merchants. Declines will never disappear, but understanding why they happen helps merchants fix what's under their control — and stop blaming what isn't. Let's look at why they happen and how they're typically classified.

Hard Declines

A hard decline means the issuer — the customer's bank — has flat-out refused the transaction, and no retry will help. Common reasons include:

- Insufficient funds or exceeded credit limit

- Expired card.

- Invalid card number (mistyped or outdated PAN)

- Lost or stolen card

- Restricted card (not enabled for certain regions, currencies, or merchant categories)

When this happens, the authorization fails immediately. The merchant can show a friendly error message, but retrying won't fix it — the customer needs to use another payment method. Many hard declines can be prevented upstream by catching obvious input errors: wrong card number length, invalid CVV, or expired cards.

Soft Declines

A soft decline is different. The issuer temporarily refuses the transaction, but a retry might succeed. These are often tied to authentication or temporary network issues, such as:

- 3D Secure authentication failure or timeout

- Issuer system unavailable

- Temporary routing or acquirer error

- Exceeded daily limit or unusual spending pattern

In such cases, the gateway can automatically re-attempt or prompt the customer to try again. Soft declines are common in e-commerce, where multiple systems and networks have to stay in sync.

Fraud-Related Declines

Then there are declines triggered by fraud-prevention systems — issuer-side, acquirer-side, or merchant-side. Examples include:

- Unusual location or device fingerprint

- Multiple failed CVV or 3D Secure attempts

- Velocity limits (too many transactions in a short period)

- Card testing by bots or stolen data

Fraud filters are constantly tuning themselves. Sometimes they block a legitimate shopper — a false positive. Finding the balance between catching fraud and allowing genuine customers through is one of the hardest challenges in payments. Some providers now let merchants adjust their own risk rules to fine-tune this balance.

Communication and Technical Errors

Sometimes, the problem isn't the card or the customer at all. Technical errors happen when a transaction message fails to travel correctly — timeouts, malformed data, acquirer outages, or protocol mismatches.

Gateways usually handle these by retrying or queuing transactions for later submission. Most are resolved quickly, but if the error strikes during authorization, the payment simply fails. For merchants and PSPs, this is the worst-case scenario — lost revenue with no clear culprit. In severe cases, such outages can even trigger penalties or service-credit claims against the party responsible.

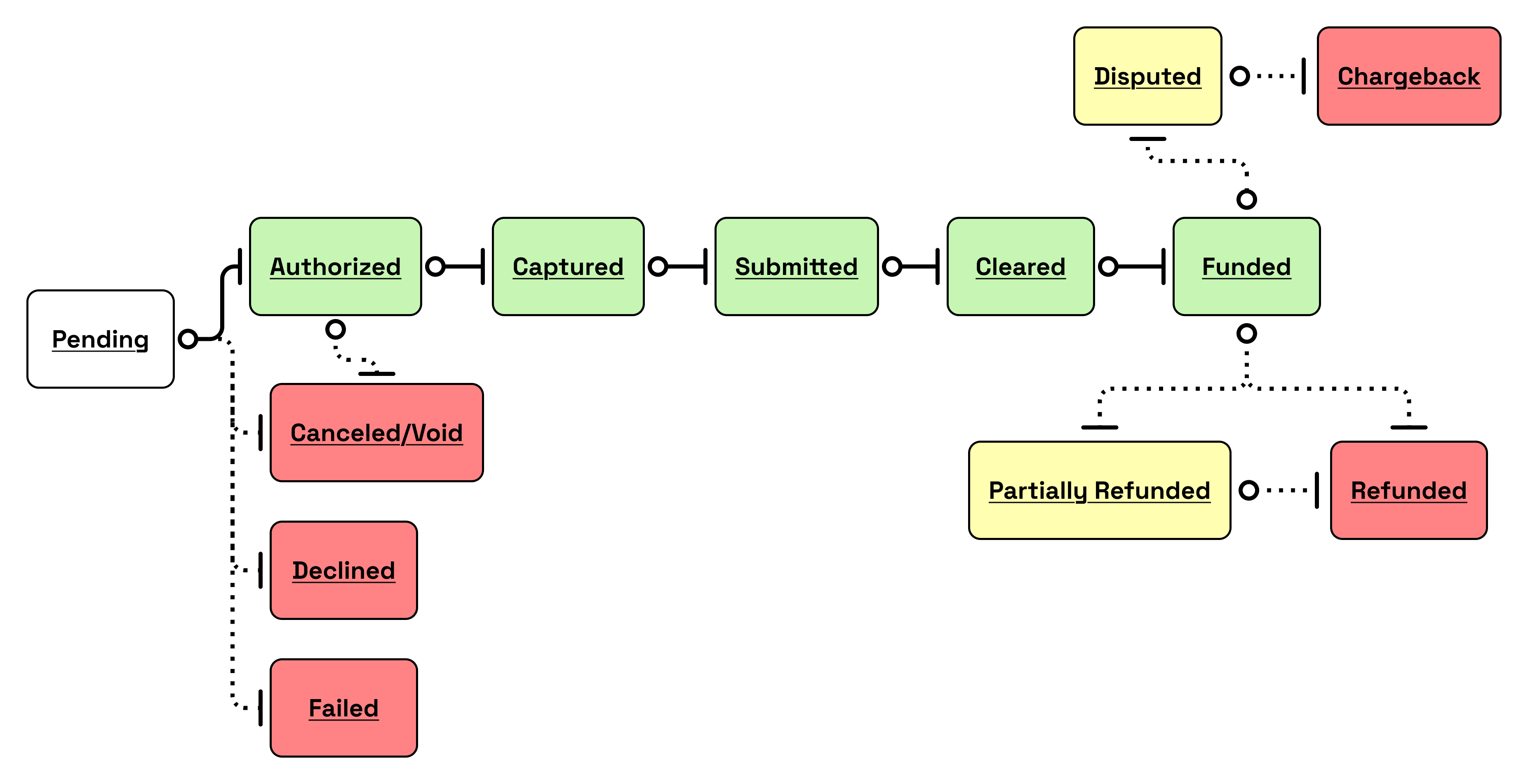

Transaction Statuses

Every payment you make or process goes through a series of statuses. Snapshots of where that transaction currently stands in its journey.

These statuses help merchants, gateways, and acquirers track progress, detect problems, and reconcile funds. While the full life of a transaction involves authorizations, captures, refunds, and chargebacks, these statuses represent the checkpoints along the way. These statuses might differ depending on the gateway or service provider. To keep it easy, I tried to summarize the statuses that exist with the table below and their flow.

| Status | Description | Meaning in the Flow |

|---|---|---|

| Pending | The transaction has just been created — either by a user, a POS terminal, or an API call. It's the very first stage, often lasting only a few seconds before moving on. | Think of it as "payment requested". Nothing has been confirmed yet. |

| Authorized | The issuer has approved the payment, and funds are reserved on the cardholder's account. The merchant still needs to capture the amount to actually receive the money. | The transaction succeeded from the customer's perspective, but it's not yet finalized. |

| Cancelled / Void | The transaction was cancelled before capture. No funds moved, and the authorization hold has been released. | Often used for cancelled orders or duplicate transactions caught early. |

| Declined | The acquirer or issuer rejected the transaction. No reservation or transfer of funds occurred. | The customer might need to try another card or payment method. |

| Failed | The transaction didn't complete due to a technical issue — maybe a timeout, network failure, or invalid message format. | No authorization response was received; it's a processing error rather than a financial decline. |

| Captured | The merchant has confirmed the transaction, and the specified amount is being processed for settlement. | The money is effectively committed and will move during the next clearing cycle. |

| Submitted | The transaction has been handed off to the acquirer for clearing. It's now in the queue to be processed through the schemes. | Between "Captured" and "Cleared". Useful for reconciliation tracking. |

| Cleared | The acquirer has sent the transaction to the schemes and is waiting for final settlement. (Planet-specific status.) | The transaction is successfully through the financial pipeline but not yet paid out. |

| Funded | The acquirer has completed the payout to the merchant's bank account. (Planet-specific status.) | The merchant has received the funds — the final financial stage. |

| Partially Refunded | Only part of the captured amount was returned to the customer. | Common when a merchant adjusts for returned items or partial cancellations. |

| Refunded | The entire captured amount was returned to the customer. | The transaction is closed from both sides; the merchant no longer holds the funds. |

| Disputed | The cardholder has challenged the transaction, and an investigation is underway. | The amount might be temporarily withheld until the dispute is resolved. |

| Chargeback | The dispute has been resolved in the cardholder's favor, and the funds have been returned to their account. | A forced refund has been processed |

Phuuu... if you made it here, congrats. Understanding statuses is probably one of the biggest challenges when wanting to understand payments.